Modern humans (Homo sapiens) first appeared in Europe 45-40,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age. The period from then until the end of the Ice Age, 30,000 years or so later, is known as the Upper Palaeolithic. At archaeological sites of this age we find beautifully crafted tools and art, alongside other evidence for complex social behaviour and specialised hunting and trapping.

The Early Modern Human Europe project is a collaboration of Eastern and Western European archaeologists working on the earlier part of the Upper Palaeolithic. This collaboration is based on the recognition that the period often saw high levels of mobility and interconnectedness of hunter-gatherer populations across Europe. Therefore, to understand the period properly, a large-scale comparative approach is necessary.

The broad questions that interest us are:

- How did people live?

- How connected were societies across Europe at different points in time?

- How did culture change during the period?

In considering these questions we, by necessity, address questions about how we carry out archaeological investigation:

- What aspects of archaeological assemblages can help us to distinguish between different groups of people in the past?

- How does the terminology used to describe archaeological artefacts and sites shape how we interpret similarity and difference between sites?

- How have language barriers and different academic traditions impacted our view of the Upper Palaeolithic across Europe?

Kostënki 17 under excavation in the 1950s. Kostënki 17 is one of the sites we have recently studied.

Our Work

The project’s members share an approach to the interpretation of archaeological evidence. First, we consider how archaeological sites and stratigraphies have formed. This allows archaeological material from one point in time to be isolated, rather than mixtures of material that may have accumulated over many hundreds or thousands of years. It is then possible to focus on the details of stone tool-making traditions, and to better fix chronology using the latest methods in radiocarbon dating. This, in turn, enables comparison between different parts of Europe through time.

Although we frequently work with recently excavated material (including from our own excavations), much of our work involves reassessment of assemblages excavated many decades ago. Reappraisal of these historic collections in the light of new methodological developments is crucial to advancing our understanding of the Upper Palaeolithic.

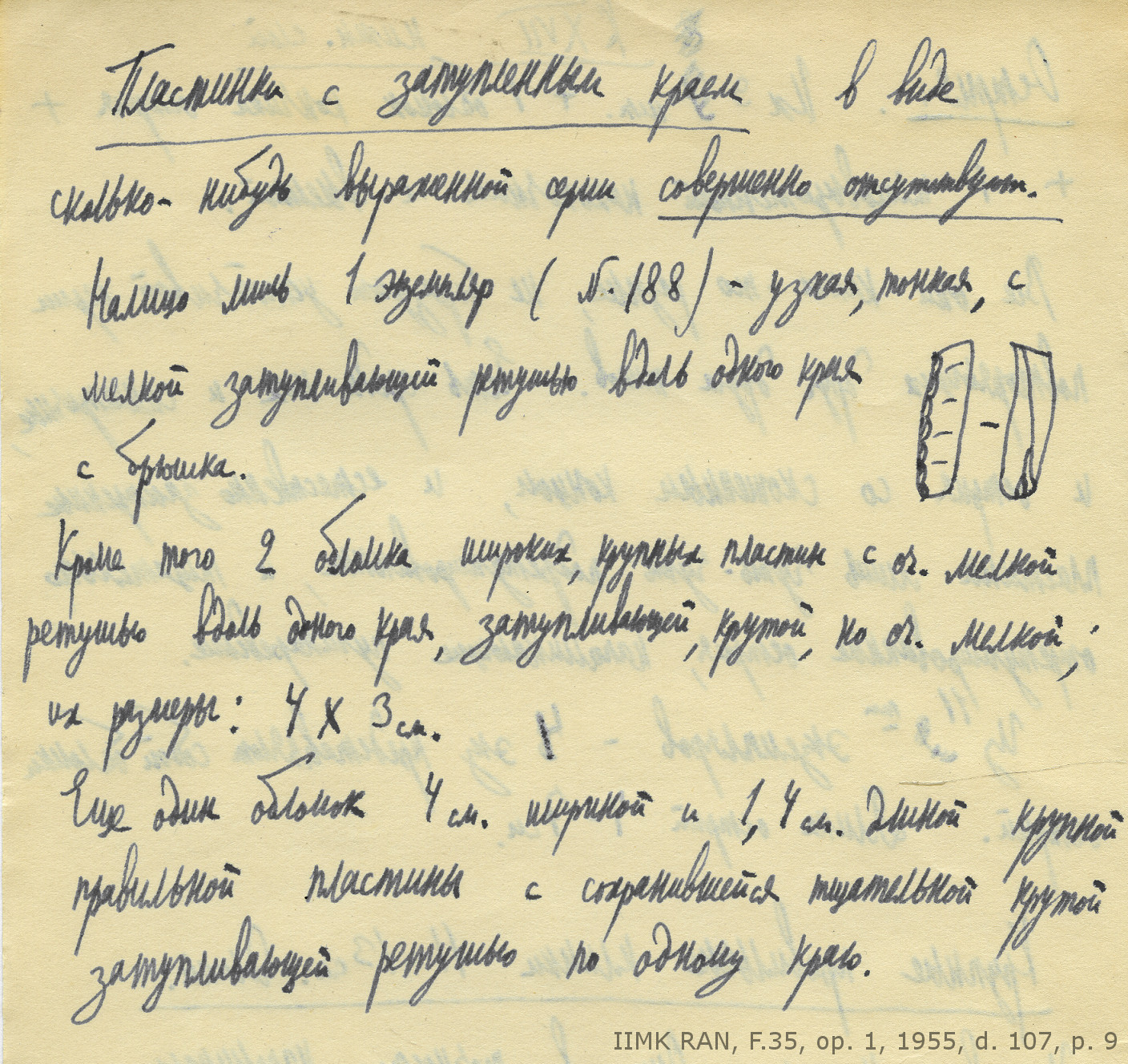

Archive documentation relating to the excavation of Kostënki 17.

Kostënki

Our recent focus has been the archaeological collections from the exceptional cluster of 26 open-air sites around the villages of Kostënki and Borshchëvo in southwestern Russia. The sites – usually numbered as Kostënki 1-21 and Borshchëvo 1-5 – have revealed habitation through the earlier part of the Upper Palaeolithic.

These sites have yielded large assemblages of bone and stone tools, accumulations of animal bones, and in some cases burials and structures. At around half of them more than one period of occupation is represented. The stratigraphic relationships between different Upper Palaeolithic archaeological cultures at the numerous Kostënki-Borshchëvo sites make the area a benchmark for understanding archaeological sites elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Much of our work is carried out at the Institute for the History of Material Culture, where many of the Kostënki collections are housed.